"I disliked in a mild, theoretical way, women in the general term": The Not-Very-Good Transmasculine Thriller of 1903

Read the original 1903 novel here.

The narrator of Six Chapters in a Man's Life, Cecil, incredibly referred to as "Cis" by his friends, is an inflexible woman-disliker until he meets the remarkable, mustachioed Theodora, whose physical as well as mental androgyny is united with Cis' Orientalism to create a sort of supercharged British imperialist crypto-homosexuality that has the potential to either save or destroy the world.

Cis is first introduced to Theodora by his friend "Digby," a sort of belligerent would-be cuckold who is determined to fix the two of them up after she has already rejected Digby, who has committed the unforgivable sin of combining a short stature with red hair. Digby goes to great lengths to persuade Cis that Theodora's mustache is serious:

"She is tall, and with a bend-about sort of figure, don't you know? I don't know what you call it. Features straight as a billiard cue, and the most thundering eyes you ever saw...I don't mind confessing to you that I am [smitten]; but it's no use. She does not see anything in me."

Hardly her fault, I thought involuntarily, glancing over my friend's five feet two of stature and head of reddish hair.

"But I should like to have the kudos of introducing you to her, I should really."

"What's the use? You know women bore me," I said, leaning back in my chair and pushing the point of my pencil idly up and down the margin of a map.

"Yes, but I should like you to see this one. She's so queer. I am not asking you to fall in love with her. I want you to see her. She's got a mustache."

I laughed. "She'd be awfully flattered if she heard you describing her," I said. "I suppose you mean a duvet imperceptible, eh?"

"No, I don't mean anything imperceptible," returned Digby doggedly, kicking the bars of the grate. "It's so perceptible that you can see it all across the room. It would spoil most women I know, but it doesn't seem to spoil her."

Eventually Cis decides he has to see the mustache for himself. He is not disappointed:

"The mouth was a delicate curve of the brightest scarlet, and above, on the upper lip, was the sign I looked for, a narrow, glossy, black line. It was a handsome face of course, but that alone would not have excited my particular attention. One sees so many handsome faces. But such a tremendous force of intellect sat on the brow, even amongst the fashionably fuzzed curls, such a curious fire shone in the scintillating eyes, and such a peculiar half-male character invested the whole countenance, that I felt violently attracted to it merely from its peculiarity."

Crypto-homosexuality, it is suggested throughout Six Chapters, can be caused by any of the following: Overwork, going to the Middle East, hot weather, insomnia, eye contact, nervous temperament.

"That intense nervous and physical excitability that I read in the dilated eyes enlisted my sympathies; perhaps because my own nerves always seemed strung to an unnatural pitch, like the overtuned strings of an instrument – the result partly, no doubt, of an irregular, ill-ordered life, and partly of fits of overwork, and principally of the organization with which I had been cursed on entering the world."

Cis is particularly taken with Theodora (later Theodore's) naturally-masculine shoulder-to-waist ratio:

"I thought I had never seen such splendid shoulders combined with so slight a hip before."

Upon subsequent meetings Cis is repeatedly persuaded of Theodora's natural, innate masculinity ("Peg" here being shorthand for a cocktail):

"Now, how ridiculous and conventional you are!" she said. "You would think nothing of letting me make you a cup of tea, and yet I must by no means mix you a peg!"

She looked so like a young fellow of nineteen or so as she spoke, that half the sense of informality between us was lost, and there was a keen, subtle pleasure in this superficial familiarity with her that I had never felt with far prettier woman.

Cis takes a detour into the question of the natural, since Theodora's "natural" hermaphroditism contrasts with his own conviction that it would be more natural to prefer a feminine woman; Theodora may be natural, but Cis' desire, while overwhelming and guided by automatic instinct, cannot be:

"This inclination towards Theodora could hardly be the simple, natural instinct, guided by natural selection; for then, surely, I should have been swayed towards some more womanly individual, some more vigorous and, at the same time, more feminine physique...

I disliked in a mild, theoretical way, women in the general term. I had an aversion, slight and faint it is true, but still an aversion, to everything suggestively, typically feminine; but Theodora, with her peculiarity, her apparent power of mind, her hermaphroditism of looks, stimulated violently that strongest, perhaps, of our feelings – curiosity."

Theodora later puts on a man's suit in front of Cis and her own sister and gets called passable (!):

"Quite passable, really," said Mrs. Strong, leaning back and surveying her languidly.

She repeats the experiment in order to travel with Cis back to Egypt, rather than be left behind when he leaves England. There's a sort of syllogism by which he cannot find another man to love enough to bring as a companion, but finds the idea of a wife impossible; Theodora solves for transmasculinity:

"I saw then that she was dressed in an ordinary suit of man's clothes and a fur-lined overcoat....

"You said you wanted to take some friend, some companion with you, only you knew no one you cared for sufficiently. Then you said it would be impossible to take a wife there, don't you remember? But you did wish there was some nice fellow who could go out with you. Well, let me come, Cecil, instead!...I have taken this dress so as to be no trouble to you. No one will know who I am, nor guess that I am a woman. Now, would they ever?"

And she stepped a little back from me and raised her face towards the light. And I looked at her, and my brain seemed suddenly to reel...The disguise was perfect, as she said. Both face and figure yielded completely to the character given them by the dress....It would have been difficult for anyone to believe that the pale, brilliant face with its straight features and dark line on the upper lip, was not that of some handsome boy of nineteen or twenty."

Cis has a strange sort of fascination with Theodora's androgyny and physical weakness – Theodore is not a robust man, and Cis often crushes his hand during handshakes, obsessively noting a sort of "bonelessness" that makes it sound like he's in love with a chicken tender:

"Theodora was tall, certainly, but without any great weight of flesh upon her. One could not say she was thin, for all her bones were so small and so hidden away in the smooth limbs that it was impossible to find one, and every joint and knuckle was only suggested by a dimple. But round and soft as an oppossum as she was in this way, she was still light and slight."

"Best of both worlds":

"It was a charming young fellow that I had beside me, with the eyes of a woman."

Cis is not alone in his admiration; on board the ship to Egypt he realizes that everybody loves a cross-dresser, and has to fight off most of the men as well as the women who hang on to Theodore's every word, which he explains away by claiming that no one cares about good-looking men in England (!):

"Theodore's brilliant face attracted some admiring glances from the men as well as the women. Male good looks are rather at a discount in England, but as one moves southward and eastward their value mounts perceptibly."

I can't recommend much of Cross' (christened Annie Sophie Cory, who wrote a lot of pulpy "New Women" novels, sometimes as Vivian Corey and sometimes as V.C. Griffin) output; the prose is always purple and the drum-beat of jingoism never very far away, but it's an interesting example of certain Edwardian ideas about the natural irresistibility of transmasculinity. Women bore me – but this one is violently queer. A mustache, you say...?

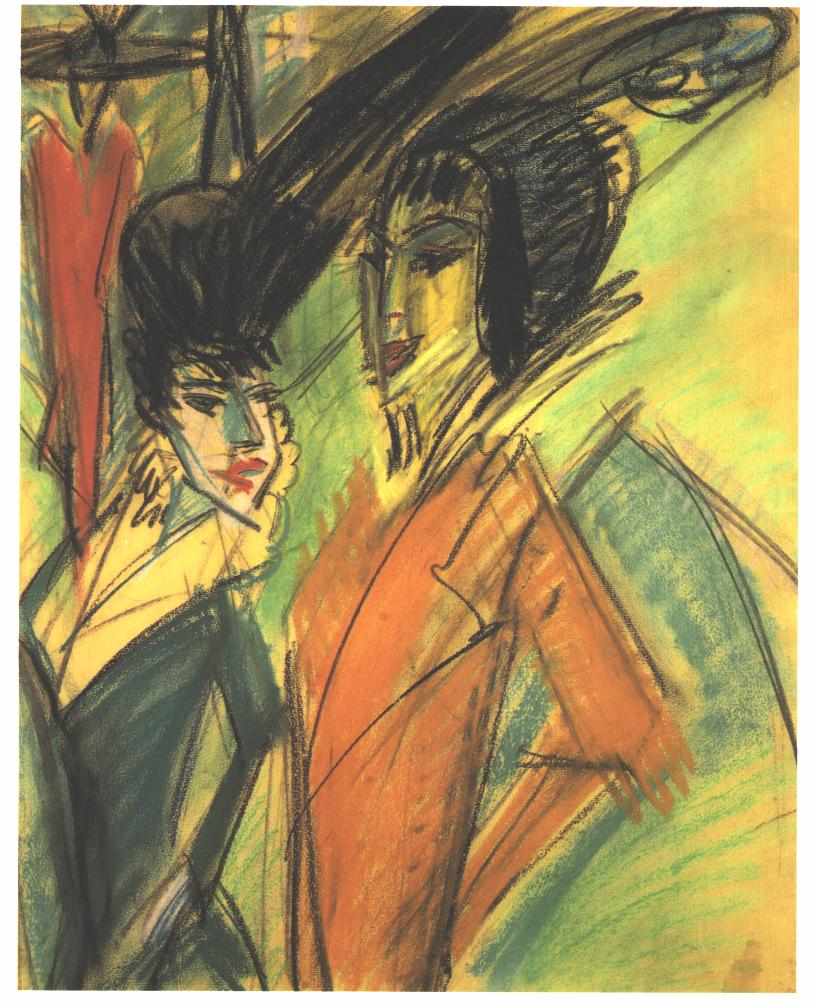

[Image via]

Comments ()