Three Eulogies

London, August 2023.

London is easy to love at this time of year. The roses are misleadingly blowsy. Earlier in the summer I flew over from New York on short notice to see my auntie, who was very ill. She was in one of the several neurology hospitals dotting Queen Square, an eighteenth century Bloomsbury beauty which is really a rectangle.

The hospital was a vast, Victorian, red brick wedding cake. In the relevant ward all the patients were unconscious so it was quiet and the nurses were kind and instead of soup and plasticine and human bodies and disinfectant it just smelled of plasticine. It poured with rain outside during my visits and the trees were writhing against the wrought iron.

She died a few days later. I had to go back to New York—I had hoped to interview Cillian Murphy for this long review I did of Oppenheimer, but at last got a firm no. Last Sunday, I showered and packed and left, and her funeral was Monday afternoon.

I followed the simplest steps between here and my parents' house: JFK to Gatwick, Thameslink to bus. From the bus I saw that it was raining again on London and that all the old grimes and glosses were reacting differently to the wet this time. Or I was just seeing it fall at 6 AM on the glazed green pub tile, the dimness under the bridge made out of morning. I met my dad for Turkish breakfast and gave him the non-vegetarian parts of mine. We walked home and I went to sleep.

An hour before the funeral was scheduled to begin, I awoke to the increasingly thunderous sound of my father calling my name up through the floorboards. I had planned to rifle through my parents’ cupboards for a blazer since the one I brought from New York was definitely navy but I had slept twice as long as I’d meant to. Flying around the cupboards I found that my parents each also owned two dark blazers that were navy, not black. I wore black jeans, the slightly navy blazer, a black tank top, and black trainers.

None of it seemed to matter in the event. Maybe it did. We drove to my auntie’s flat to meet my siblings and their babies and then we walked down the road to the church. This again.

Through the glass doors with some kind of cheerful welcoming Christian message, and the worn maroon carpet, the dust in the sunlight, the pulpit and its forceful inhabitant: Three funerals. All in the same crematorium afterwards, too, the same grave and stately disruption of traffic with the hearse at the roundabout. My grandfather, who was really my step-grandfather; his wife, who was my grandmother, my father’s mother; and now my father’s sister. He has a couple of living cousins but otherwise that’s it for his lot.

We went to the front pews and put our stuff down then got back up to greet the mourners. I shook hands with her cousin, her friends, and several of the lovely older people who lived in the same block of flats. My auntie had planned her funeral very precisely.

The priest got things going. He was animated and nice. We stood to sing the opening hymn, “How Great Thou Art.” The priest told us to sit. My dad stood up and walked up the red carpet steps to the clear lectern. He told the story of her life in facts. She was born in May 1952, to an English mother and a South African father. At one point their family of four had ten citizenships between them. She was baptised and later christened in the Methodist Church.

The family lived in rural Namibia until the death of my paternal grandfather in the late summer of 1955. My grandmother and the two children moved first to Port Elizabeth in South Africa, and then inland to a drier area, in an attempt to lessen to my aunt’s suffering with asthma. She survived her childhood to read English and religious studies at the University of Cape Town and the history of art as an independent adult student. She moved to London in the early 1980s, where she worked as a secretary in the City of London.

My aunt’s main interest in her life from her teenage years onwards, my dad explained to the people in the pews, was her profound, positive and vibrant faith in God. He was putting that part mildly. He noted her love of studying genealogy and the two volume book she wrote; her fascination with the Tudors and in particular the personality and works of Henry VII. She was generous and eccentric and funny and a great friend. Many had written to him as the news of her passing spread.

My aunt lived her life on her own terms, he concluded, and was happy, contented and fulfilled. She knew that she was unwell, but she felt a release and a joy at the prospect of moving to a different spiritual plane. “We grieve her loss today but she felt only joy and happiness for the eternity that was coming to her.”

He walked down the shallow red steps. I stood up. I gave him a hug as we passed and then I was behind the lectern. I speak in front of people all the time. It doesn’t even give me dread in advance any more. Not because of being good at it but just from teaching. So I was shocked to hear my voice wobble. Faces. Some small smiles of encouragement, I thought, from the nice people from the block. But as I started to describe our slightly complicated relationship I felt a little zap of tension in the church—unaccounted for, possibly just the inaudible squeak of molar on molar.

I thanked them all for coming to remember my aunt with us. My siblings and I grew up with our parents not far from where my auntie settled in London, I explained, and we saw her every Sunday for lunch with our parents and grandparents and spent every Easter and Christmas together. She was gentle and kind, the intellectual and connoisseur among us, and we were never in any doubt of her love for us.

To a child any adult from outside the nuclear family is a mystery, I said. but my auntie was genuinely different from anybody else I knew. Small and softly spoken, for the most part, behind her subtle presence was a spirit and will of uncommon strength. She lived independently, for example, in the years before moving in with her parents. She never married. I didn't mention her thoughts on my own marriage. She was always kind to my face.

She loved tennis and Formula 1 motor racing. But nothing was more important to my auntie than her relationship with God, I said. I think everybody who knew her respected her profound and certain faith, and throughout my life she frankly discussed what she heard and saw and felt of the divine in the world around us. Again, this was an understatement. It feels wrong to speak about her beliefs, I said, because for my auntie God was a fact who made his reality abundantly known.

I told them about her love of theatre, in particular the works of William Shakespeare, also established early and consistent throughout my aunt’s life. She took me to see my first Shakespeare play, Cymbeline, at the Barbican, in the mid-1990s, and over the years along with various family members we saw Richard II at the Old Vic, Hamlet at the National Theater, and many others. We always talked about the production at the interval and after it finished and she would tell me stories of other productions she had seen over the years. She had sat in every one of the cheapest seats at all the major theatres of London, it seemed, and seen every great stage actor. She remembered details of their interpretations; the sad take on a joke, the tragic speech delivered like a punchline.

My auntie’s other great creative hero was Bob Dylan. Her favorite song, I’m pretty sure, was “Black Diamond Bay,” and the three albums he made during his conversion to Christianity were close to her heart. But she knew his entire catalogue back to front. The highest compliment that she could pay to a piece of art was that it made you sit up and realise, days later, that there had been some hidden double or triple meaning to a lyric. This was the defining feature of Bob Dylan and Shakespeare alike, for my auntie, I think—the way a simple act of words can take on infinitely different meaning, depending on what day you consider them. In her love for both of these artists, my auntie modeled for us how to cultivate a private and in-depth appreciation of the art you love.

Putting a very complicated thing simply, I said that my auntie had prevailed against health problems from an early age that surely played a hand in the development of her robust and inspired inner life. But whatever the struggle before her, my auntie exuded the confidence of a person who knew with unshakeable certainty what her place was in the universe and the role of love in putting her there. In closing, I hoped that she might inspire us all to stick to our guns, build the life that we want, not the one that others want for us, and to notice the divinity in the ordinary world all around us.

I took one step to the right and then about six down the stairs to the second-to-front pew, where I sat down, relieved, and thought about her. The third speaker went up the steps. He was a good friend of my aunt’s. Very tall and with a Christian beard.

My aunt loved our Lord, he began explaining. And she would call him and his wife on the telephone, and they would have the most beautiful conversations, and recently, he remembered, they were discussing what the world has come to when people can’t decide if they’re a man or a woman! He laughed, as he described how they laughed and other people laughed, because he hit it like a comic beat. Then he stared right at me and smiled hard. mostly I think people were confused. Then he carried on with his reading.

That week I had been feeling smug about getting a Google alert telling me I had a Wikipedia page now. It’s helpful for trying to get jobs and I need a job. But maybe this brimstone moment was the result of the page, which might give a person with a cellphone too much information, summarized too briefly, organized too strangely, delivering just enough basis for loathing to disrupt one single London funeral.

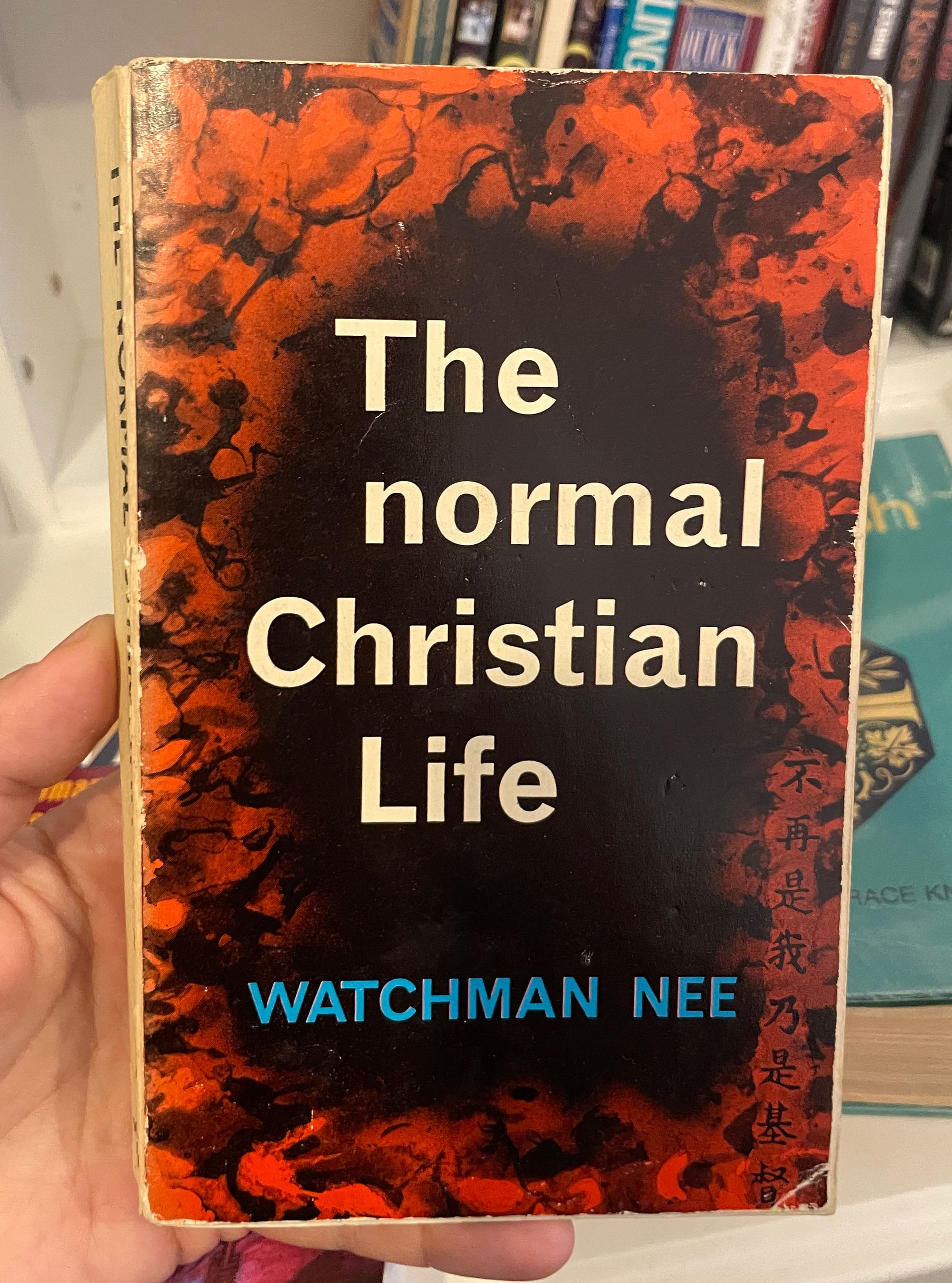

It was too silly to be that upsetting but the afterglow of the sting sort of obliterates my memory of the rest of the funeral. The tea went well and so did lunch, afterwards, where my uncle, who is a doctor, explained that the catty fundie had been telling him about the effectiveness of his healing prayers on legs of uneven length. Back at the flat, rummaging my auntie’s bookshelves freely for the first time, I got some great stuff about hell and detective novels for me and three old Angela Thirkell editions for Danny. My auntie left all of her suprisingly substantial life savings to an evangelical television station.

Comments ()