Free Writing Advice: Jo and Danny on going long

Jo: Daniel! Welcome back. You’ve been on a long writing voyage and I’m on the shore with my hanky. I don’t know what they used to say when ships came in. ”Oh!” And then, probably, “Welcome back.”

Danny: Robert Benchley had a great old column about how tired he was of going down to the docks to meet friends getting off ships during a visit to New York City. And I wish I too was tired of seeing ships off and welcoming them into harbor! But it never happens to me. Yes, I’ve finally written a book! I have written books before but they were almost all jokes or short stories or even shorter essays, so I never had to write a full novel’s worth of words before. It takes a while!

J: It’s a lot of words, for sure. I think it must be very different to attack a project having already published books, writing a novel. After I got laid off I did one but it was like jumping out of a window more than going on a trip. But seeing you rampage through this novel brought me to think about how much I admire your work ethic. I’ve been working on something longer than usual and I wondered if I could press you on some aspects of the process. I think the parts of your experience that are not that relatable to the average striver are like: being really organized and productive, knowing it’s going to end, that kind of thing. So, if you had to not reference, like “process” in terms of scheduling, but instead reached for more general observations—what is your experience this time around with working with a big bathtub of words?

D: I do feel admired, thank you! I’ll preen briefly. Then I’ll try to answer your question. I didn’t try to write a novel until I had been writing professionally for over a decade, so I do think it helped to approach the idea of writing a novel very slowly and very indirectly, for fear of startling myself. And I do credit getting one of my professional starts, if only briefly, at Gawker under the remarkable Max Read, who helped me cultivate real discipline when it came to reaching a daily word count, and I came to learn that it was a skill that could be cultivated like any other.

When I sold the novel, it was only as a proposal with two sample chapters—I think about 10,000 words. The contract specified the final manuscript had to be 80,000 words. Then I wrote two more chapters in about two weeks, bringing it up to 22,000 words and a loose outline of the plot, so that I had a rough idea of what else was going to happen. Then I thought about it and didn’t write anything else for maybe four months (not substantial, anyhow. I did a lot of light reading about the period, since the book is set in the mid-60s, and working on character sketches). So I wrote the bulk of the novel between May and September of this year, aiming for a daily word count of 2,000 most weekdays. Some weeks I did just that; towards the end it was closer to 3-4,000 words a day, to make up for the lighter weeks earlier in the summer, which was a little hard on my hands. If I had it to do over again I’d do a little more earlier and a little less later. But I came in at 80,522 words and only five weeks late, which isn’t too bad, I think.

J: Danny, it’s incredible—so much as to be, I think, not that relatable? Because a lot of people could follow just that schedule and it would not work, from the deal to the last day of what you typed. This is really common among exceptional brains, I think; that tiny slippage between what part is the bit that makes you different and what is the part that is the same as a lot of other talented people, and it’s fascinating in itself.

That intervention is to ask—and this is me grabbing at the thing I am either projecting or reading between the lines—is this the classic sequence that occurs when a great writer has a great idea, suppresses it slightly while working on other stuff, and then it all comes out, having brewed subconsciously and/or in unwritten form for a long time? And if so, is that common for your longer stuff? Pushing it back until the time comes, I mean. (Thinking also of your recent gorgeous Pepin piece for the NYRB.)

D: Well, I’ll happily preen again at that, but I do think there were a few factors very much in my favor: I had a deadline with money attached to it, which is very motivating, and my other day jobs all involve being at home and writing, so I didn’t have to work around a commute or a 9-to-5, which facilitated things very nicely indeed. I don’t think I often suppress great ideas—if anything my fault lies in the other direction, and I churn out a lot of possibly-decent ideas at a rapid and half-baked rate. Both my better qualities and my faults lie in the same quadrant; I can generate a lot but I find sustaining ideas a little difficult. Once I have a good idea, I think, half the work is already over. If the idea doesn’t strike me in the right way, it feels impossible to write about; if it does, I can type until my hands hurt. I should have been a newspaperman in the 20s!

It also helped to break the book down often into smaller chunks. It’s about a women’s hotel, so it was a bit like Grand Hotel or Dinner at Eight—lots of little plots coming together, which meant I could take it easy and one stage at a time. Writing a chapter a week isn’t too daunting, I think, if you’ve got a good idea. And for me, writing begets more writing, and ideas beget more ideas. I write better when I’m writing a lot (even if a lot of what I’m producing isn’t ultimately publishable). Now I have a proposal and sample chapter for my next novel, and a pretty good outline for the next three, assuming my agent likes them.

J: Money is so motivating, that’s so true. The sustaining idea thing is compelling to me, too.

When I have a great idea or come across somebody else’s underrated great idea that I want to describe (only the latter happens) I often sense it as a great oppressive heavy anvil sitting on top of my head until it’s processed. It’s a feeling of obligation: I have to be spending my time with this, I should be spending my time with it. I’m not sure what that compulsion is called? It definitely comes out of love, but it takes the affective structure of duty, which is silly because it’s obviously a low-level duty if it is one at all. This has been the case with a profile I’ve been working on recently, which is long-ish and has been scary to undertake. The sustaining idea in this piece has been the fact of my own genuine addiction to the subject and its (ostensible, to me, right now) explanatory power about everything.

And so for one of the first times ever I have been held up by anxiety—not about writing, because I can churn it out like anybody who has done this for a job for a while, and I do know what you mean about writing generating more writing—but about doing the subject justice. Because the idea belongs to the world??

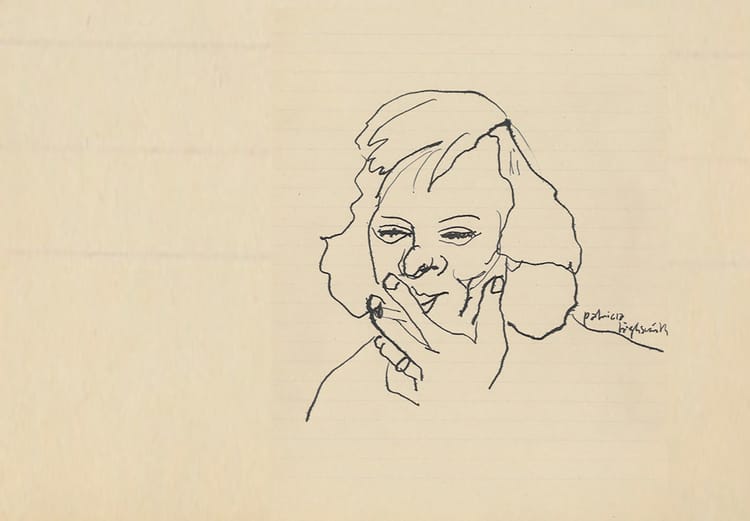

Ok I’m reminding myself of this graphic that Charlotte Shane beautifully captioned in her recent newsletter:

This blog (TheStopgap.net) helps a lot with that stuck feeling, for me—a reminder that nothing matters and that writing something for no reason is exactly as fun as all other kinds of writing sentences.

But actually there’s a question for you here, which is: Talk to me about your relationship to nonfiction vs fiction? Shout out to Max Read for tipping you into journalistic writing. But there’s a fuck of a lot of research and reading that seeps out into even the lightest and most speculative of your writing. I especially love your essentially fictionalised relationship to those newspapermen of the 1920s—you connect with them at the level of form, which is more newspapermanlike than being a historian of print culture or whatever the most formal version of that work would be.

D: Journalistic at best, to be clear—I’ve never committed an act of real journalism. And I think what you experience as that obligation, even duty, I sometimes experience as urgency.

I haven’t seen the exact quadrants before, but I think I have a general sense of that breakdown—areas where you know you’re incompetent versus areas where you don’t.

I like fiction quite a lot; I think the bulk of my humor writing has been fictional, broadly. For what it’s worth I don’t think I do research; I do background reading sometimes, but there’s no system or method or expertise that amounts to research, I don’t think. And I find it incredibly difficult to describe places, for some reason. “There’s a building…they’re inside it…don’t worry about it.”

J: Gosh, I would love to write places for you that you could choose from a menu eg

- Abbey

- Hovel

- Extinct agricultural setting

- Night

- Day

- Some kind of in between

- Cold and dry

- Cold and wet

- Indoors but something howling

- Empty but for you

- Populous

- Five hiding enemies

- Seaside

- Windowside

- Bedside

- Art deco

- Hewn from landscape

- Memphis

I feel like I’m not asking the right questions. It’s possible that you and I just don’t speak the same language when it comes to longer stuff but meet in the short? My fears are not your fears; my joys not your joys. So to be straightforward, if you had to speculate about what you’ve learned in writing this longer thing from scratch that you didn’t know before, how’s that?

D: Oh wow, I find this menu thrilling. Please write five of them for me to structure books around, and one more for us to publish on the Stopgap, thank you in advance.

I think it’s true that we have very different fears – possibly because you have already written a dissertation? That’s the sort of length that would frighten me very much indeed, where I feel like I tricked myself into writing a novel by adding a lot of short stories together – a great many shortnesses, rather than a single great length, if that makes sense.

J: Totally, but the dissertation is like bowling with the bumper lane things on, or appearing to make an amazing marble sculpture but you’ve just put plaster of paris on top of chickenwire then varnished it. The structure is prefabricated and you can cling to it all the way to the winners’ podium. You’ve been bowling the adult way this whole time.

So I think the best way to do this might be for you to send me an image of some weather and a brief description of a character and then I’ll put them together. And then the final product will automatically be longer than either of us could possibly have written on our own.

D: I could never install chickenwire or put plaster of Paris on anything. Here is a picture of some weather. Here is a description of a character: The least fastidious man in the French Foreign Legion.

Comments ()