How to Cheat at Reading and Writing

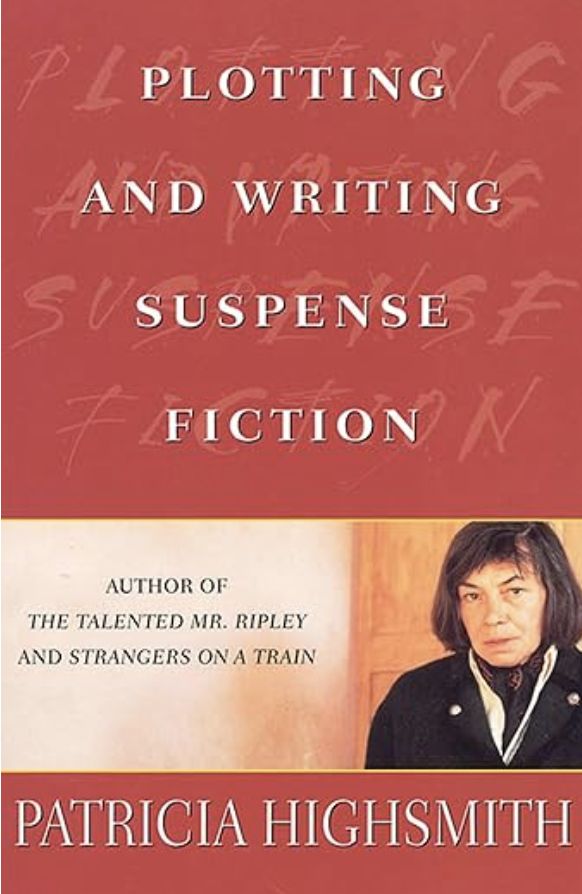

There’s only one good book about how to write: Patricia Highsmith’s Plotting and Writing Suspense Fiction. Some particular gems:

“It is then good to remember that artists have existed and persisted, like the snail and coelacanth and other changing forms of organic life since long before governments were dreamed of.”

“I had depressing thoughts that the theme, even though I had thought of it, was better than I was as a writer. Henry James or Thomas Mann could easily write it, but not I. 'I'm thinking of writing it from the point of view of someone at the hotel who observes her,' I said, but this did not fill me with much hope. Then my friend, who is not a writer, suggested I try it from the omniscient author's point of view.”

There are a lot of people out there who can already tell you how to write the normal way. It’s probably best to listen to them. Or avoid them. I don’t know. But as I was walking my dog just now I was thinking about how often I’ve explained the following few tips to friends and students. I don’t know if they’ve found them helpful, I just know that I’ve explained it a lot. I’ve explained it a lot because they ask. They ask because I read and write fast.

I have a few principles that work unfailingly, except where I fail the principles, which guarantees failure. Do not deviate from the order

1. Understand that it is possible to cheat, but that it is not even considered cheating.

This is an important idea to get ahold of, because the following tips aren’t even illegal in writing. Become comfortable with your criminality. This will help you feel comfortable with showing other people an unfinished piece of work, which will be necessary for implementing tip 2.

2. The deadline is much, much more important than the words.

I know that blowing deadlines is the chief anxiety of many writers. Unfortunately, I come here to tell you that they are correct to worry.

Imagine that you were an engineer who had to deliver a project draft by a certain date. You would turn in whatever you had, in lieu of a final product, on the date agreed upon by all the parties you are working with. I don’t know why this has become such an unclear issue in writing in particular—as a writer I obviously feel that the responsibility lies with editors.

But you have to hit your deadline. If you are not finished, send them what you have. A lot of writers I think are worried about showing something that they think is terrible. But the fact is that the editor can rewrite absolutely anything if she needs it fast enough—anything except nothing. Nobody can edit nothing. I promise you that your writing is not good enough that the first draft will be perfect, so why be embarrassed? This is one of those things like being naked around other people socially that require you to simply get over it if you want to be at the commune.

3. Practice speed-reading

You can follow the instructions in books and online and stuff, but the aim of speedreading practice is always the same: To put your eyes on the page in a different pattern than the classic left-to-right, every-line zigzag motion of normal reading.

To discover what shape works best for you, learn through practice. Start by trying to read whole clauses at once, moving your eyes from single point to single point on either side of a comma or question mark or similar. The key is to let yourself believe—and I am convinced that this is true of a very large proportion of people, in my experience including some dyslexic readers—that your mind can extract information from a set of words without doing it consciously or from left to right (presumably in Arabic or Hebrew this would work the other way around).

Convincing your unconscious mind takes you almost all the way there. Next you can try doing whole sentences. Try an author who uses short or clear sentences, like Patricia Highsmith.

Eventually you’re going to put this technique of leaping from static point to static point in motion. Your mind will tell you how. For me, it’s a figure 8. I start at the top left of the page and then kind of imagine that I’m reading the whole page as a single sentence; down diagonally from top-right to bottom-left, then to bottom-right, then back up to pick up the stuff I’ve missed.

It should go without saying that you should not do this with novels, because there is no point. But for anything that you have to read in a time sensitive fashion, you can absorb about, in my experience, 70% of the content. This makes you reasonably prepared for a conversation about a book after speedreading it.

4. Speed-reading + healthy respect for deadlines = ready to learn speed-writing

If you practice writing one form enough—the ~1300-word review article, say, or the five paragraph essay they make you write at American universities—you can cultivate a kind of speed-writing that comes from being intimately familiar with its structures. If you practice writing out different ideas the same way over and over again, you can consciously learn to map in advance where the things you’ve gleaned from your speed-reading will go on the page, in approximate order. This is what I call ‘everything at once’ writing and it signifies having successfully become a cheat.

Congratulations!

Comments ()